Monks’ unpaid work: counted

The day-to-day life of a religious community is rarely the focus of an economic analysis. Recently, however, Brother Ignác D. Tamás OSB and Ágnes Szukits, Head of the Department of Strategic Management at Corvinus University of Budapest, did exactly that in their latest paper published in the newest issue of Budapest Management Review. The authors examined how the economic value of monks’ work carried out without pay can be estimated.

The research centres on the thousand-year-old Saint Mauritius Monastery in Bakonybél in Hungary and the nine monks working there. A distinctive feature of the Benedictine Rule is that it includes an economic mindset: it explicitly aims for the monastery to be independent and self-sustaining, and not overly reliant on donations. The activities carried out by the Bakonybél monks, ranging from growing medicinal herbs and making jams to bronze work, and running the shop and guesthouse, would amount to paid jobs in most organisations. Here, however, all of this forms part of service to the community. That does not mean the work has no price. The analysis does not quantify the value of spiritual activities; instead, it focuses only on the community and economic work that can be expressed in monetary terms.

A monastic hourly wage of HUF 2,411

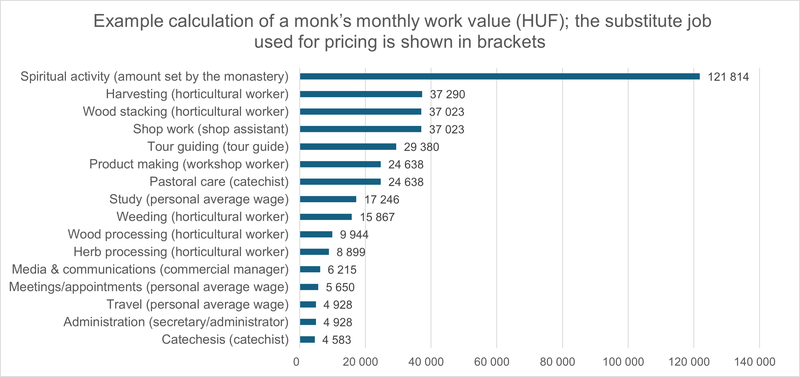

To produce their estimates, the authors used a hybrid methodology. Where a clear market substitute existed (for example, horticultural staff or shop assistants), they used the relevant wage costs as a benchmark. In other cases, they used the monks’ alternative (foregone) income-generating time as the point of comparison. For spiritual programmes offered to others, they relied on the monastery’s own internal pricing practice.

According to the results, the average “monastic hourly wage” is HUF 2,411. This represents the cost the monastery avoids by not employing external labour. For the nine monks, this amounts to around HUF 400,000 per person per month, or approximately HUF 3.7 million worth of work in total carried out without pay.

The monastery underprices

On an average day, the monks spend three hours in prayer and seven hours working. More than two-thirds of their working time is spent on religious services, administration, maintenance of the monastery, operations, and planning – activities that do not directly generate revenue. Only two revenue-generating activities appear among the ten most time-consuming tasks: work in the shop and production (such as herbal products, jams, syrups, mustard, and silversmithing pieces).

“Only about half of the costs incurred in the monastery are built directly into products and services, so their prices do not cover the value of the monastic labour invested. As a result, the community, despite selling ‘a little cheaper’ in line with monastic tradition, may expose itself to financial risk in the longer term,” says Ágnes Szukits, one of the authors and Associate Professor at Corvinus.

In the spirit of the Benedictine Rule

Benedictine tradition emphasises both self-sufficiency and moderation: monks live from the work of their own hands, but they do not overprice what they sell: “they are truly monks when they live by the labour of their hands.” While pure profit maximisation is entirely alien to the monastic outlook, the study argues that long-term self-sufficiency depends on the monks at least consciously recognising the real value of their unpaid work for their community.

Monasteries are “hybrid organisations”: both religious communities and economic units that operate on a non-profit basis, but still have to think in market terms to remain sustainable. Monastic work is a lifelong commitment without formal employment frameworks, differing from classic forms of volunteering, yet in several ways resembling the logic of household labour or family businesses.