Cold is more dangerous for the heart than heat

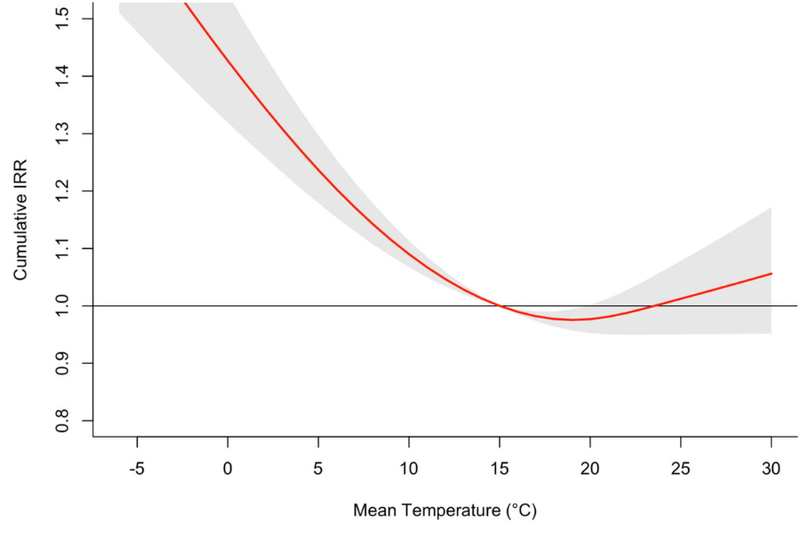

Researchers from Semmelweis University, Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, the University of Pannonia and the National Ambulance Service compared temperature data with more than 116,000 cardiac arrest cases over a five-year period. Their findings were published in the January issue of the journal Resuscitation Plus. The results show a U-shaped relationship between temperature and sudden cardiac arrest. The lowest risk was observed at around 19°C; as temperatures moved either colder or hotter, the number of cases increased. The largest rise in risk was linked to cold spells lasting at least three days, although sustained heatwaves above 27°C also showed a significant increase.

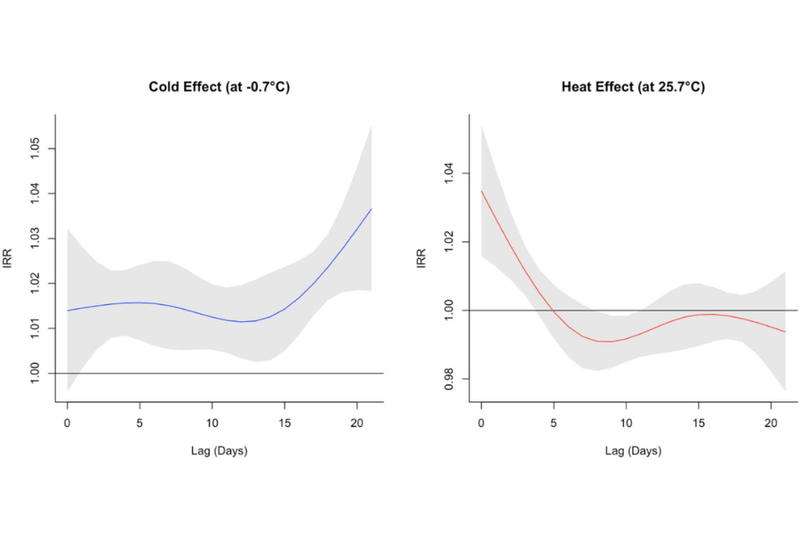

The researchers identified an important difference in the way heat and cold affect the body. Heat acts quickly and for a short time (up to one week), typically peaking within three days and then fading. In contrast, sustained cold below −9°C for at least two days has a delayed effect, usually appearing after around three days, and places a longer-term strain on the body, potentially increasing risk for up to two weeks after the cold period.

“Unlike many previous studies, we also showed that cold days defined in a similar way to heatwaves—when the temperature falls below −10°C—carry an additional risk, which calls for more flexible warning systems. We have also previously confirmed that prolonged cool days similarly increase the risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” said Brigitta Szilágyi, Associate Professor at Corvinus University and a co-author of the study.

Different physiological processes are likely behind these effects. Heat can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and heart rhythm disturbances, while cold stresses the body through blood-vessel constriction, increased blood pressure and a higher tendency to form blood clots. Humidity, sunshine or isolated hot days on their own showed no association with the number of cardiac arrests, and the effects did not differ between women and men.

The researchers say the findings have practical implications. During heatwaves, healthcare services need to respond rapidly, while cold periods require heightened readiness for longer. On an individual level, the most effective steps are adequate fluid intake and reduced physical exertion in hot weather, and in cold weather regular blood pressure monitoring and protection against the cold to help reduce risk.

Cumulative association between daily mean temperature and cardiac arrest risk over a 21-day lag, estimated with distributed lag non-linear models. The curve shows a U-shaped relationship with lowest risk at 19.0 °C (minimum mortality temperature). Risk increases towards both heat and cold extremes, with steeper effects for cold. The red line indicates the estimated cumulative IRR; gray shading indicates 95 % confidence intervals

Temporal patterns of cardiac arrest risk associated with cold (left) and heat (right) exposures over a 21-day lag, estimated with distributed lag non-linear models. Curves are shown relative to the minimum mortality temperature (19.0 °C, IRR = 1.0). Heat (95th percentile, 25.7 °C) produced an acute, short-lived increase in risk, whereas cold (5th percentile, −0.7 °C) produced a delayed and more persistent elevation in OHCA case incidence. Solid lines represent mean estimates; shaded areas show 95 % confidence intervals.