How Can We Avoid Being Dragged Down by “Organisational Sludge”? – Mats Alvesson Presented His New Book at Corvinus

In his lecture at Corvinus University of Budapest on 16 September, the Swedish professor discussed the background of this frustrating phenomenon, which undermines the efficiency of both organisations and individuals. He also shared advice on how to avoid being pulled under by the sludge ourselves. The professor returned to Budapest as a visiting researcher at CIAS, where he led a research seminar, held a workshop, and offered consultations organised by the Institute of Strategy and Management, and also spent a day with members of the Rajk College for Advanced Studies.

His talk was full of vivid, personal examples as he introduced the main ideas of the book he co-authored with André Spicer, The Art of Less: How to Focus on What Really Matters at Work. Alvesson, professor at Lund University and also teaching part-time at the University of Bath and City University of London, is the author or co-author of more than thirty books, including the widely discussed The Stupidity Paradox.

Their new book highlights a problem most of us will find familiar today. At work, employees often feel weighed down by too many initiatives, meetings, trainings, and targets. Overzealous leaders, interfering consultants, and stakeholder groups with competing demands frequently get in the way of “real work.” As a result, people feel overloaded while at the same time less productive.

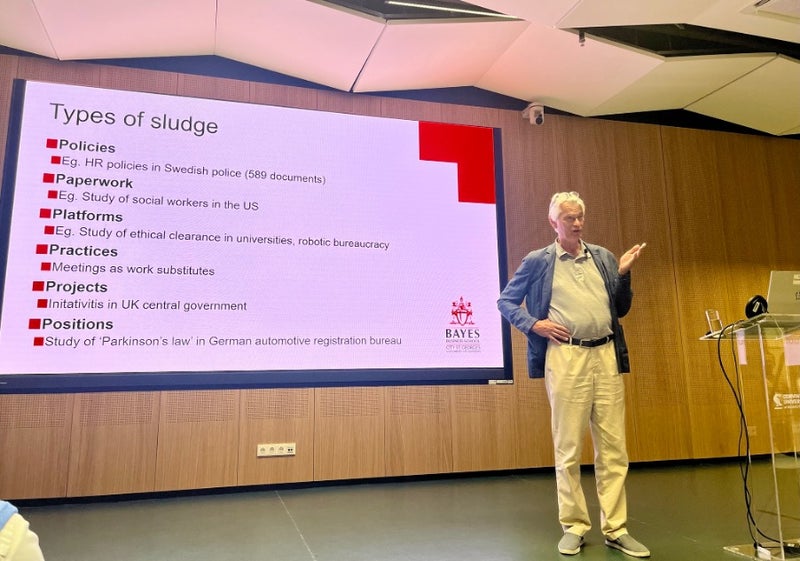

A key focus of the lecture was the definition of “sludge” – a mix of processes, rules, and requirements that restrict people’s ability to act. Once caught in this sludge, workflows break down or slow to a crawl, making it extremely difficult to focus on core tasks and value creation. The book provides concrete examples of how organisations and companies become overcomplicated, offering too many products or services, which eventually blocks efficient operations.

Alvesson cited a UK study showing that medical interns spend 80% of their working hours on tasks not directly related to patients. While some administration is necessary, such proportions raise questions about whether they are healthy. Academia is not spared either: at many elite US universities, there are now more staff in administrative positions than in teaching and research roles.

The business sector shows similar symptoms. The rapid growth in the number of managerial roles is one indicator, while research by the Harvard Business Review revealed that only 13% of respondents felt bureaucratic processes had decreased, and 40% said the most common procedures do not really help but instead prevent them from doing their jobs.

In his lecture, Alvesson also pointed to factors that accelerate the growth of sludge, such as meetings, unnecessary documentation requirements, excessive regulation, and bureaucracy in general.

Finally, he outlined ways to resist the pull of organisational sludge. These included tactical measures – like ignoring or avoiding the factors that create it – as well as broader strategies, such as appointing “sentinels” to monitor and limit its spread. He closed with an encouraging example from Dutch intensive care units, where a thorough review process successfully reduced the number of quality indicators from 122 to just 17, showing that effective action against sludge is possible.