Even a small design change can alter perceptions of organic food

Researchers from Germany, the UK and Hungary found that even small graphic tweaks in the labelling of sustainable foods can significantly influence consumer trust and willingness to buy. The study was conducted by the University of Bonn, Newcastle University and Corvinus University of Budapest as part of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme, and the results were published in the journal Agribusiness.

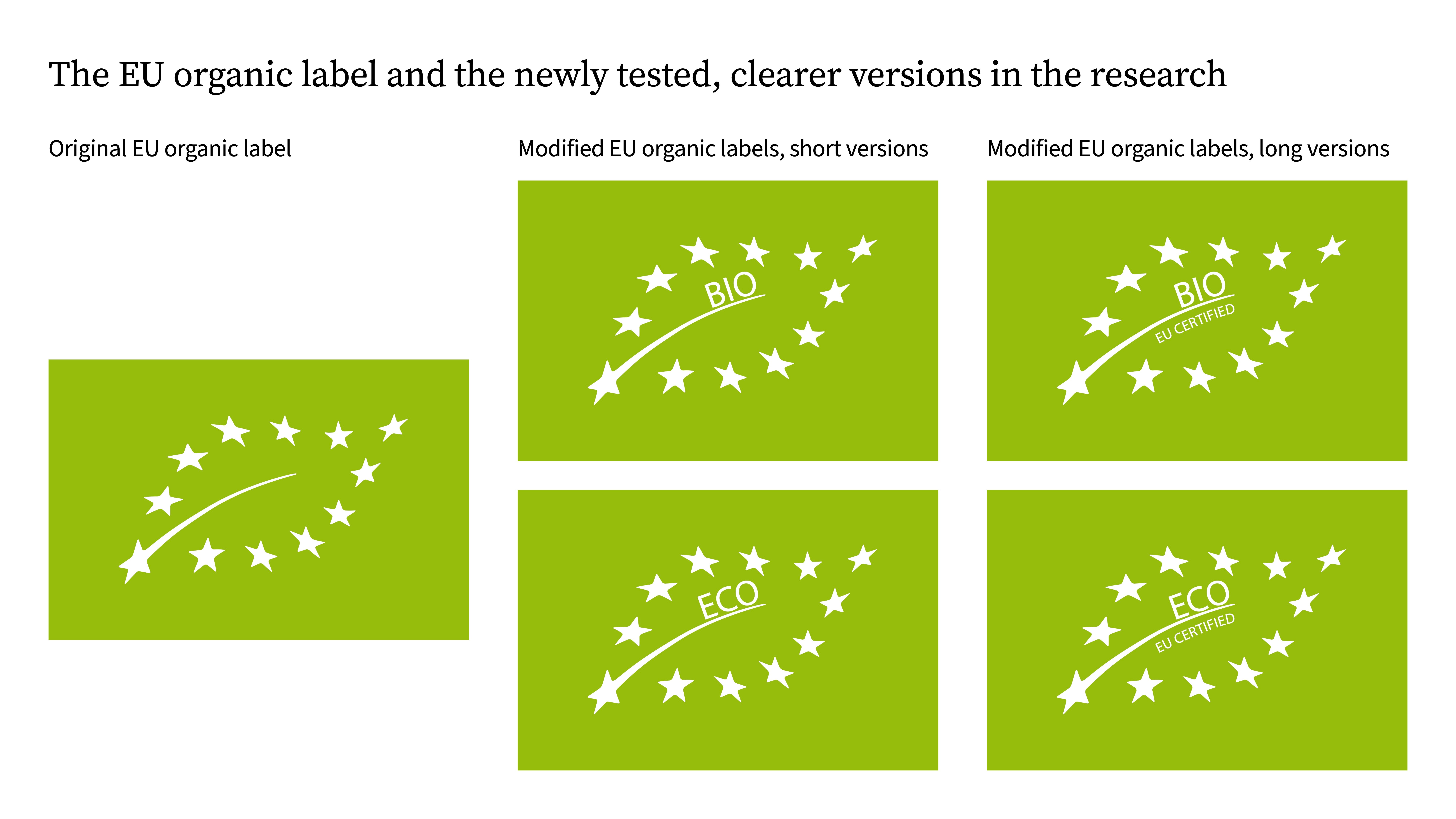

At the centre of the research was the EU’s green leaf organic logo. Since 2010, this label has been mandatory on all pre-packaged products that contain at least 95 per cent organic ingredients. Yet only 56 per cent of EU citizens recognise it, and an even smaller share – just 45 per cent – know exactly what it means. Labels like this are meant to assure consumers that products meet certain social and environmental standards.

The survey, which included over 9,000 participants from seven European countries, compared the standard green leaf logo with two modified versions. One included the word “BIO” and the other “ECO – EU certified” in the local language. Participants were asked to rate whether they found the logos clear, trustworthy and helpful in making informed choices. The results showed that even small changes reduced consumer uncertainty, improved understanding of the label and boosted purchase intentions. Both modified versions were rated clearer, easier to understand, more reliable and more useful than the original. Interestingly, adding the “EU certified” note did not provide additional benefits.

Abstract symbols limit effectiveness

“Sustainability labels can help consumers choose socially beneficial and environmentally friendly options. But confusion about what they mean undermines their effectiveness, especially when the logos are abstract,” said Áron Török, professor at Corvinus University of Budapest. “If consumers don’t fully understand the labels, they tend to undervalue them. That’s why it’s important to recognise that small changes in colours, images or wording can strongly influence reactions. It’s worth testing different versions to achieve greater impact,” added his co-author Matthew Gorton, research professor at Corvinus and marketing professor at Newcastle University.

The study found similar results across all seven countries examined (France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Norway, the UK, and Serbia), regardless of cultural or economic background. This suggests that making labels clearer could be a universally effective strategy for encouraging sustainable consumption.

The article also presents a related experiment involving around 500 German participants, which looked into why the modified versions were more effective. The findings showed that the logos became much easier to interpret. “Nearly 90 per cent of respondents correctly linked the versions containing ‘BIO’ or ‘ECO’ to organic products. By contrast, fewer than 70 per cent identified the original EU logo correctly,” said Monika Hartmann, lead author of the study from the University of Bonn.

Incremental changes rather than replacement

The researchers warn that introducing a completely new logo could be risky, as it might reduce the recognition already built up and impose extra costs on producers. By contrast, slight adjustments to the existing label could improve its effectiveness at relatively low cost, though they would still require regulatory changes and packaging redesign.

The results carry an important message for EU policymakers: if sustainability labels are to truly support environmentally friendly consumption, attention must be paid not only to the strictness of regulation but also to the clarity of communication.